Ethical Lens Inventory (ELI)

D. Reflect on your Ethical Lens Inventory (ELI) by doing the following:

1. Explain your preferred ethical lens, or what it means to have a center perspective relevant to the ELI. a. Analyze whether you have the same preferred lens in different settings (e.g., work, personal, social).

2. Explain both your primary values and classical virtue(s) from the ELI. a. Compare two primary values and one classical virtue from part D2 individually with three of the top five values from the Clarifying Your Values exercise.

3. Describe one of the following from the ELI: your blind spot, risk, double standard, or vice. a. Discuss three steps you can take to mitigate the blind spot, risk, double standard, or vice described in part D3 in order to make better ethical decisions in the future.

4. Discuss how you plan to use the ethical lens(es) to approach ethical situations throughout your professional life.

You have a considered preference for the value of autonomy (CA)—respecting the individual—over equality—giving priority to the group. As a CA, you are committed to choosing your own path and seeking your own truth while considering the opinions of others and general community expectations about what constitutes a "principled life." You wholeheartedly defend the right of every human to choose how they will live into their full potential as they seek their own expression of the good life.

Know Yourself

Pay attention to your beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors.

The first step to ethical agility and maturity is to carefully read the description of your own ethical lens. While you may resonate with elements of other lenses, when you are under stress or pressure, you’ll begin your ethical analysis from your home lens. So, becoming familiar with both the gifts and the blind spots of your lens is useful. For more information about how to think about ethics as well as hints for interpreting your results, look at the information under the ELI Essentials and Exploring the ELI on the menu bar.

Understanding Your Ethical Lens

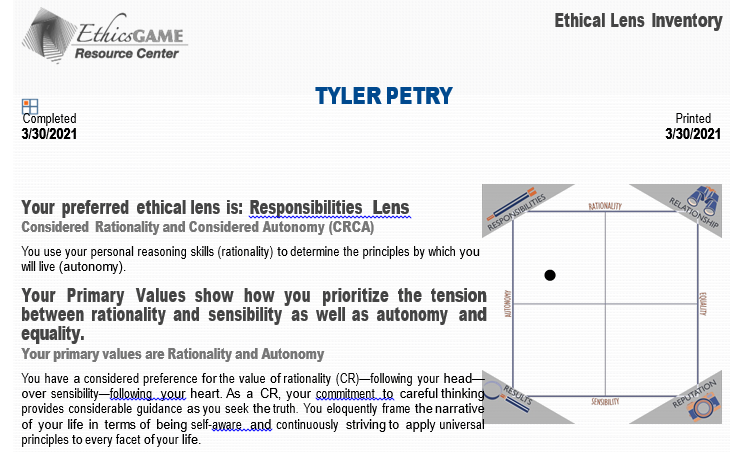

Over the course of history, four different ethical perspectives, which we call the Four Ethical Lenses, have guided people in making ethical decisions. Each of us has an inherited bias towards community that intersects with our earliest socialization. As we make sense of our world, we develop an approach to ethics that becomes our ethical instinct—our gut reaction to value conflicts. The questions you answered were designed to determine your instinctual approach to your values preferences. These preferences determine your placement on the Ethical Lens Inventory grid, seen on the right side of this page.

The dot on the grid shows which ethical lens you prefer and how strong that preference is. Those who land on or close to the center point do not have a strong preference for any ethical lens and may instead resonate with an approach to ethics that is concerned with living authentically in the world rather than one that privileges one set of values over another.

Each of the paragraphs below describes an ethical trait—a personal characteristic or quality that defines how you begin to approach ethical problems. For each of the categories, the trait describes the values you believe are the most important as well as the reasons you give for why you make particular ethical decisions.

To see how other people might look at the world differently, read the descriptions of the different ethical lenses under the tab Ethical Lenses on the menu bar. The “Overview of the Four Ethical Lenses” can be printed to give you a quick reference document. Finally, you can compare and contrast each ethical trait by reading the description of the trait found under the Traits menu. Comparing the traits of your perspective to others helps you understand how people might emphasize different values and approach ethical dilemmas differently.

As you read your ethical profile and study the different approaches, you’ll have a better sense of what we mean when we use the word

“ethics.” You’ll also have some insight into how human beings determine what actions are—or are not—ethical.

The Snapshot gives you a quick overview of your ethical lens.

Your snapshot shows you living responsibly into your principles.

This ethical lens is called the Responsibilities Lens because people with this focus value having the right to choose how to responsibly live into their principles—even if other people don’t always agree with them. They care primarily about living into their own core principles, the Truth as they see it.

The Responsibilities Lens represents the family of ethical theories known as deontology, where you consider your principles—and the duties that come from those principles—to help you determine what is ethical.

Your Ethical Path is the method you use to become ethically aware and mature.

Your ethical path is the Path of the Thinker.

On the ethical Path of the Thinker, you use your reason to identify the principles—the foundational rules—that you believe are worthy of adoption and will lead you to the Truth. As a human being, you have the privilege of choosing how best to live your life. Your preference is determining for yourself the principles that you believe are the most important. Then you determine how your actions can be true to your guiding principles.

As you walk the Path of the Thinker, you pursue your quest for the truth. In the process, you expect that the world will make sense as you ground your principles in human dignity and uphold the freedom of every person to use their reason to determine how best to live as a person-in-community.

Your Vantage Point describes the overall perspective you take to determine what behaviors best reflect your values.

The icon that represents your preferred vantage point is a telescope.

Just as a telescope helps you see the farthest points on your journey and gathers all of the available light to help you see long distances, the Responsibilities Lens helps you take a long view and identify the ideal principles that are important for human beings.

Your Ethical Self is the persona the theorists invite you to take on as you resolve the ethical problem.

Your ethical self is a universal rational self, outside of a particular place or time, seeking ideal principles that apply to everyone.

Using the telescope of the Responsibilities Lens, you think of yourself as a rational person who has no particular identity and does not consider the specifics of the situation, including your own preferences. Because your principles—such as “do no harm”—provide all the guidance you need, you do not give much weight to prior experience in determining which duties to follow.

Because you strongly believe that everyone has the right to use their own reason to follow their own truth, you give others great freedom to live into their identified universal principles. You also expect that each person will make their own decisions based on agreed-upon principles so power will not be abused by either individuals or the community as a whole and everyone’s rights as a human person will be honored.

Your Classical Virtue is the one of the four virtues identified by Greek philosophers you find the most important to embody.

Your classical virtue is prudence—making wise decisions in everyday affairs.

As you seek ethical maturity, you know you should embrace prudence, making wise choices within a specific context and begin to listen to your heart and develop empathy for those affected by your decision.

Noticing the problems caused by pride and anger, you seek to moderate your principles to ensure your actions make sense within a given context. You also strive to control your self-righteousness through developing empathy for others.

Your Key Phrase is the statement you use to describe your ethical self.

Your key phrase is “I am responsible.”

You value personal autonomy and rely on your capacity for reason and critical thinking. Thus, while you listen to others, you still cherish the choices you make. Having chosen, you take responsibility for your actions—and expect others to do the same. And, as you seek meaning in life by living into your principles and embracing your duties, you find that you delight in your work and it provides great satisfaction.

Using the Responsibilities Lens

By prioritizing rationality and autonomy, the Responsibilities Lens provides a unique perspective on what specific actions count as being ethical. This lens also has its own process for resolving ethical dilemmas. As you translate your overarching values into actions—applied ethics—each perspective provides a particular nuance on what counts as ethical behavior. This next section describes how you can use the Responsibilities Lens to resolve an ethical dilemma.

Deciding what is Ethical is the statement that describes your preferred method for defining what behaviors and actions are ethical.

You decide what action is ethical by identifying the overarching principles by which you will live.

With a considered preference for rationality, you value your reason and vision to help determine the principles by which you will live. You strongly believe that an action is ethical if it fulfills your considered responsibilities as an ethical actor, is done with care and concern for the other person, and contributes to you delighting in your work and activities.

Your Ethical Task is the process you prefer to use to resolve ethical dilemmas.

Your ethical task is to identify principles that guide appropriate action.

Your primary focus is seeking the Truth. As you gaze through this lens, you follow your head—reason—to resolutely choose the principles, the ethical norms, that you believe are worthy of adopting. You have faith that those who also seek the truth will find the same principles.

You also strongly believe that each person has the privilege of engaging in the search and defining for themselves what a meaningful life entails, even if others would not make the same choices that you do.

Your Analytical Tool is your preferred method for critically thinking about ethical dilemmas.

Your preferred analytical tool is reason.

You determine what is true by using primarily reason and research. You begin with an assessment of current knowledge as well as your feelings about the subject. Then use your own reason, tempered by emotion as well as the carefully thought out opinions of others, to work through the ethical dilemma.

You highly value self-management and can self-soothe when faced with the inevitable storms of life, even if you are working with others who may not share your sense of duty or understand your motives.

Your Foundational Question helps you determine your ethical boundaries.

Your foundational question is “What are my reasons for this choice?”

As you ask, “What are my reasons for this choice?” you take time to identify your principles, examine your motives, and determine what agreements with others you should keep. Any path forward must meet the ethical minimum of having your motives for acting be those you are consistently willing to hold in every similar situation. You give yourself and others a healthy amount of freedom to identify the principles and reasons for any particular ethical act.

Your Aspirational Question helps you become more ethically mature.

Your aspirational question is “What is a caring response?”

As you expand your perspective to include others, you begin considering what motives for action others might find acceptable. You ask, “Am I willing for others to have the same motives when deciding how to treat me?” Asking this question allows you to pause and see the humanity of the other person, reducing your chances of being brusque and judgmental.

And then, as your perspective shifts to include all people and seek a greater purpose in life than only caring for yourself, you begin to moderate your considered preference for rationality and autonomy as you ask, “What actions will help me act with integrity and support living into my ideal vision?” Asking this question allows you to develop perspective instead of pettiness as you reflect on the meaning and purpose of your life.

Your Justification for Acting is the reason you give yourself and others to explain your choice.

Your justification for acting is “I was being principled!”

You like to explain your choices by announcing that you have thoughtfully considered your ethical obligations. As long as you meet your own expectations of your core ethical principles, you believe that you have met your obligations.

At your best, you responsibly embrace adulthood, cheerfully meeting the considered responsibilities of a fully engaged member of the community. You know that you have many options for action, even after you have eliminated actions that you consider wrong or that don’t reflect your principles.

Strengths of the Responsibilities Lens

The ethical perspective of the Responsibilities Lens has been used by many over thousands of years to provide a personal map toward ethical action and personal fulfillment. Striving to be consistent as you follow clear principles is an effective strategy for managing desires, finding meaning in your life, and getting along well with others.

Your Gift is the insight you provide yourself and others as we seek to be ethical.

Your gift is self-knowledge.

Because you have researched every situation, you bring the gift of autonomy and responsibility to your community as you discern what action is appropriate. As you gain ethical maturity, you develop the gift of empathy, tempering your actions with caring. As you grow in self- knowledge and gently come to terms with your own and others’ imperfections, you learn to live in the present. The strength of your convictions gives you the ethical courage needed to act in a meaningful way.

Your Contemporary Value is the current ethical value you most clearly embody.

Your contemporary value is to seek the truth.

You are actively committed to live into the timeless universal principles that allow you to use those ideals to become the best person you can be. That commitment, however, is tempered by a moderate privilege of autonomy—the right of people who recognize that they are a person-in-community to determine for themselves what is “true.” You expect people to take the opportunity to look for the truth behind their actions as each is encouraged to live from a position of integrity.

As you move from private action to public policy, you begin to moderate your own understanding of the truth to consider the knowledge and principles of others. As you consider others, you find a principle-based approach to ethics useful, carefully assessing which commonly held principles will allow others to develop trust in you. At your best, you are self-disciplined and keep your promises. In the process, you live a consistent life, grounded in carefully considered principles.

Your Secondary Values are those that logically flow from your primary values.

As you harmonize autonomy and rationality, your secondary values focus on choosing consistent actions to support a meaningful life.

Your journey on the Path of the Thinker involves embracing consistency and authenticity. You promote life and safety, making sure that people do not have their lives unknowingly endangered. You practice truthfulness as you believe that people have a right to not be intentionally deceived by others. Finally, you respect privacy, as you support people having the right to do whatever they choose in their private lives as long as others are not harmed.

Challenges of the Responsibilities Lens

One of the greatest challenges of the Responsibilities Lens is recognizing that you can never be perfectly rational because, as a human, you regularly make decisions that are inconsistent with your stated beliefs and preferences. With a considered preference for both rationality and autonomy (CRCA), you are vulnerable to the ethical blind spots of the Responsibilities Lens that come from relying primarily on your own reason as you define an authentic life.

Using the telescope of the Responsibilities Lens to see where you are not living into your own ideals helps you avoid ethical blind spots that come from a lack of self-knowledge.

Your Blind Spot is the place you are not ethically aware and so may unintentionally make an ethical misstep.

Your blind spot is the belief that motive justifies the method.

With confidence in your reasoning ability, you begin to believe that your carefully reasoned motives justify your method for accomplishing your goals. Believing your actions are flowing from universal principles, you grudgingly consider people’s responses to your beliefs or your actions. With little empathy, you may forget to test your action against the very real consequences that will cause people upset and pain.

Being insensitive to the emotional climate of the situation, you may discount the signals that you receive from others that you are being overbearing. Finally, trying to meet the requirements of every principle, you may become legalistic and then take on more and more responsibility as you fail to reflect on the meaning and purpose behind your activities.

Your Risk is where you may be overbearing by expecting that people think just like you.

Your risk is being autocratic, or in common terms, bossy.

Believing you know what is right, you are surprised when others don’t agree with your definition of duty. Without the humility of noticing that you may not always be right, you run the risk of becoming autocratic as you adopt a “my way or the highway” approach to ethical decision making.

Because the principles you live by are universal and self-evident, you fully expect everyone to make the same choices as you judge whether they have measured up to your ethical standards.

Your Double Standard is the rationalization you use to justify unethical actions.

Your double standard is excusing yourself from following the rules.

Humans are skilled at deflecting blame if caught being unethical—taking actions that do not live into their own stated principles and thus eroding trust in the community. As you view the world through the Responsibilities Lens, you judge others by their adherence to your principles.

When tempted to be unethical, your ethical spin will often be excuses—giving reasons that you believe justify failing to live into your own values. You may insist that you are being true to your core principles—even when a reasonable person can see that you are not being your best ethical self. You will convince yourself that the rules were meant for other people, or that the action you took really did meet your responsibilities—even though your ethical self tells you otherwise.

Your Vice is the quality of being that could result in you being intentionally or carelessly lured into unethical action.

Your vice could be allowing pride and vanity to make you judgmental and legalistic.

While unethical action can come from being unaware, humans also have moral flaws that, if not acknowledged, may turn unethical choices into habits. Because you have a considered preference for rationality, you are susceptible to the vices of pride and vanity. Without awareness and reflection, you can become judgmental and legalistic, certain that you are better than others.

With a considered preference for autonomy, you are susceptible to the vices of anger and untrustworthiness. Without self-knowledge, humility, and compassion, you can become rigid in your own definition of the truth, quick to label others as unethical if they are not fulfilling their duties—as defined by you.

Your Crisis is the circumstance that causes you to stop and evaluate your ethical choices.

Your crisis could be precipitated when you become exhausted.

As you continue to walk the Path of the Thinker, you will at some point face a personal crisis as you acknowledge your inability to live into strongly held ideals. Believing you can do anything by yourself, you become so committed to fulfilling your duties that you become exhausted.

Confronted with an unraveling of your world, you may wind up on a slippery slope to unethical behavior—not thoughtfully shedding some of the responsibilities we have embraced may help us live into our highest principles. Many who have been found guilty of violating someone’s trust began with cutting one small corner that they thought that they could “make right” without anyone knowing the difference.

Strategies for Ethical Agility and Ethical Maturity

Resolving ethical conflict is an ongoing as well as challenging task. Because our personal morals and community ethics come from our deeply held values, we must approach the problems mindfully. Great self-knowledge helps us identify the values that are in conflict. Listening respectfully to others as they express their preferred course of action based on their core values also helps. Seeking harmony between our personal expectations and the behavior that the community rewards enhances ethical effectiveness and leads to ethical maturity, the ability to live in personal integrity while respecting the value priorities of and caring for both other individuals and the community as a whole.

Ethical agility is measured by our ability to use all four ethical lenses effectively. We develop ethical agility as we practice looking at the world through different ethical lenses, become more aware of the places where we are tempted to be unethical, and remember to ask the core questions that define each ethical perspective.

Follow the checklist for action

Ethical courage involves not just analyzing and reflecting—but also taking action. Pausing to check a proposed action against the value priorities of the Responsibilities Lens is a good final step for people from every ethical perspective. Using the checklist from each lens ensures a balanced decision, one that considers the core values and commitment of each lens.

Remember to do what is right even if no one is watching. As a responsible person, follow the principles that are important to you. Focus on the ideals you want to realize. Don’t get discouraged by the current condition of your world. The purpose of ethical action is to help create a world where the spirit of the principles for action are followed and we can all live in a better place.

Ask people how they want to be treated. Each person is an individual who deserves respect. By asking them how they want to be treated, what behavior counts as living out their principles, you can tailor your response to meet both sets of ethical expectations. Treat people as “fully functioning adults.” Assume that every person is committed to being responsible and living out their core values, which includes accepting the consequences of their actions.

As you become skilled at using your ethical telescope to identify the ideal principles that guide you on your path, you will find yourself in good company with others who follow the Path of the Thinker on their journey through life.

Develop ethical agility

Ethical agility is the ability to use all four ethical lenses—and the center perspective—effectively. You become more ethically agile as you practice looking at the world through different ethical lenses, become more aware of the places where you are tempted to be unethical, and remember to ask the core questions that define each ethical perspective.

Recognize the language of the different lenses

As you read about different approaches to ethics, you can pick up the subtle clues to other people’s ethical perspectives by the words they choose to describe the problems and the reasons for their proposed course of action. To learn more about the other ethical lenses, read the information about each ethical lens under the tab Ethical Lenses on the menu bar or review the descriptions of the ethical traits for each lens under the tab Traits. You can also print the document “Overview Four Ethical Lenses” found under the Ethical Lens tab to have a quick reference guide to all four ethical perspectives.

Use all the ethical perspectives

Each ethical lens has a unique perspective on both the way to solve a problem as well as the specific characteristics of the most appropriate solution. To learn more about how each ethical perspective approaches ethical dilemmas, click Lens in the top navigation bar and read through the descriptions of each ethical lens.

Ethical agility is the first step towards ethical maturity, a life-long process of becoming ever more self-aware and learning how to move with dignity and grace in our community. As we move from fear into confidence, from thinking only of our self to considering others and the community as a whole, we gain ethical wisdom—a primary task of life as we seek that which is True and Good to find the Beautiful.

If you want to learn more about the how to understand and effectively use your ethical profile, please refer to The Ethical Self, by Catharyn Baird and Jeannine Niacaris (2016).