Global Networks Assignment

Assignment

For this assignment, you will create a slideshow based on some of the ideas contained in a video that you will watch.

Step 1

Watch the video, Globalization I - Crash Course History, below. Notice when narrator John Green draws your attention to a t-shirt, which happens to be merchandise for the Crash Course History series. You will have to understand that he does not merely include the t-shirt for promotional purposes. Instead, it operates as a symbol of globalization itself.

Step 2

Your slideshow will answer this question: In what way does the t-shirt in this video represent and explain globalization?

Your exploration of this topic will include the following:

● Globalization includes winners and losers and it always has.

● Textiles have a long history within global trade.

● Understanding globalization requires understanding global supply chains and having access to shipping channels.

● The story of globalization is also the story of industrialization, technology and their developments

Step 3

Create your slideshow using this format.

1. Title slide with presentation title, your name and the date. This slide could include an image.

2. Introductory slide in which you introduce the entire topic

3. Main body of 5-7 slides in which you cover the points above in the best order for maximum impact. Each slide must have at least one image that helps to explain your exploration of the topic. You must make direct reference to what is said in the video and may reference the course materials in this section.

4. Concluding slide in which you summarize and wrap up your topic.

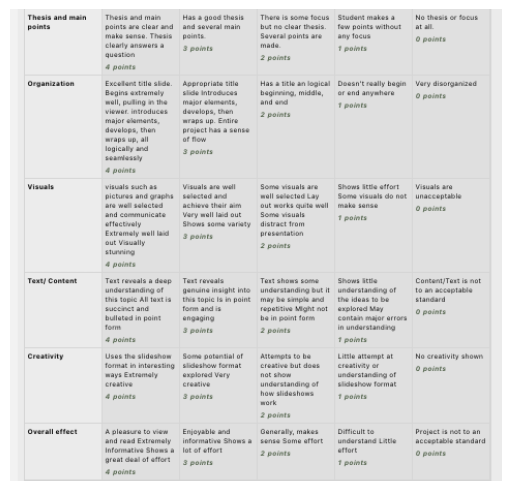

This will be marked according to the rubric below.

Course Readings

So, when did international trade start and how did it lead to globalization?

In this section, you will learn that international trade began at least 2000 years ago. This is when the first goods from China begin to show up in Europe. At this point in history, international trade was minuscule in comparison to local trade, yet it was significant as it was the beginning of a trend that would increase for centuries.

By the Age of Exploration, when large wooden sailing ships began to plow the seas, taking one set of goods with the trade winds to Asia, and another set back as the winds became favourable back to Europe, international trade became big business, allowing some families, and some nations, to increase their wealth in a way that the world had never seen before. Most of the

world's increasing population at this point, however, still lived lives that were unaffected by these goings on.

It was really after the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century when the first wave of true globalization appeared. What marks the turning of events here was global communication systems as well as technology which allowed for the shipping of everyday items such as fruits and meat to be shipped from South America to North America and Europe. Once Costa Rican bananas and pineapples were showing up in New Brunswick and companies in South Africa could speak with buyers in France and Germany, a new world had come into being.

Soon enough, multinational companies dominated world markets. Computers and the creation of the internet didn't create these global networks but sped them up exponentially.

Silk Roads

People have been trading goods for almost as long as they’ve been around. But as of the 1st century BC, a remarkable phenomenon occurred. For the first time in history, luxury products from China started to appear on the other edge of the Eurasian continent – in Rome. They got there after being hauled for thousands of miles along the Silk Road. Trade had stopped being a local or regional affair and started to become global.

That is not to say globalization had started in earnest. Silk was mostly a luxury good, and so were the spices that were added to the intercontinental trade between Asia and Europe. As a percentage of the total economy, the value of these exports was tiny, and many middlemen were involved to get the goods to their destination. But global trade links were established, and for those involved, it was a goldmine. From purchase price to final sales price, the multiple went in

the dozens. The Silk Road could prosper in part because two great empires dominated much of the route. If trade was interrupted, it was most often because of blockades by local enemies of Rome or China. If the Silk Road eventually closed, as it did after several centuries, the fall of the empires had everything to do with it. And when it reopened in Marco Polo’s late medieval time, it was because the rise of a new hegemonic empire: the Mongols. It is a pattern we’ll see throughout the history of trade: it thrives when nations protect it, it falls when they don’t.

Spice Routes (7th-15th Centuries)

The next chapter in trade happened thanks to Islamic merchants. As the new religion spread in

all directions from its Arabian heartland in the 7th century, so did trade. The founder of Islam, the prophet Muhammad, was famously a merchant, as was his wife Khadija. Trade was thus in the DNA of the new religion and its followers, and that showed. By the early 9th century, Muslim traders already dominated Mediterranean and Indian Ocean trade; afterwards, they could be found as far east as Indonesia, which over time became a Muslim-majority country, and as far west as Moorish Spain.The main focus of Islamic trade in those Middle Ages were spices. Unlike silk, spices were traded mainly by sea since ancient times. But by the medieval era they had become the true focus of international trade. Chief among them were the cloves, nutmeg and mace from the fabled Spice islands – the Maluku islands in Indonesia. They were extremely expensive and in high demand, also in Europe. But as with silk, they remained a luxury product, and trade remained relatively low volume. Globalization still didn’t take off, but the original Belt (sea route) and Road (Silk Road) of trade between East and West did now exist.

Age of discovery (15th-18th) Centuries

Truly global trade kicked off in the Age of Discovery. It was in this era, from the end of the 15th century onwards, that European explorers connected East and West – and accidentally discovered the Americas. Aided by the discoveries of the so-called “Scientific Revolution” in the fields of astronomy, mechanics, physics and shipping, the Portuguese, Spanish and later the Dutch and the English first “discovered”, then subjugated, and finally integrated new lands in their economies.

The Age of Discovery rocked the world. The most (in)famous “discovery” is that of America by Columbus, which all but ended pre-Colombian civilizations. But the most consequential exploration was the circumnavigation by Magellan: it opened the door to the Spice islands, cutting out Arab and Italian middlemen. While trade once again remained small compared to total GDP, it certainly altered people’s lives. Potatoes, tomatoes, coffee and chocolate were introduced in Europe, and the price of spices fell steeply.

Yet economists today still don’t truly regard this era as one of true globalization. Trade certainly started to become global, and it had even been the main reason for starting the Age of Discovery. But the resulting global economy was still very much siloed and lopsided. The European empires set up global supply chains, but mostly with those colonies they owned. Moreover, their colonial model was chiefly one of exploitation, including the shameful legacy of the slave trade. The empires thus created both a mercantilistic and a colonial economy, but not a truly globalized one.

First Wave of Globalization (19th Century - 1914)

The first wave of globalization roughly occurred over the century ending in 1914. By the end of

the 18th century, Great Britain had started to dominate the world both geographically, through the establishment of the British Empire, and technologically, with innovations like the steam engine, the industrial weaving machine and more. It was the era of the First Industrial Revolution.

The “British” Industrial Revolution made for a fantastic twin engine of global trade. On the one hand, steamships and trains could transport goods over thousands of miles, both within countries and across countries. On the other hand, its industrialization allowed Britain to make

products that were in demand all over the world, like iron, textiles and manufactured goods. “With its advanced industrial technologies,” the BBC recently wrote, looking back to the era, “Britain was able to attack a huge and rapidly expanding international market.”

The resulting globalization was obvious in the numbers. For about a century, trade grew on average 3% per year. That growth rate propelled exports from a share of 6% of global GDP in the early 19th century, to 14% on the eve of World War I. As John Maynard Keynes, the economist, observed: “The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole Earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep.”

And, Keynes also noted, a similar situation was also true in the world of investing. Those with the means in New York, Paris, London or Berlin could also invest in internationally active joint stock companies. One of those, the French Compagnie de Suez, constructed the Suez Canal, connecting the Mediterranean with the Indian Ocean and opened yet another artery of world trade. Others built railways in India, or managed mines in African colonies. Foreign direct investment, too, was globalizing.

While Britain was the country that benefited most from this globalization, as it had the most capital and technology, others did too, by exporting other goods. The invention of the refrigerated cargo ship or “reefer ship” in the 1870s, for example, allowed for countries like Argentina and Uruguay, to enter their golden age. They started to mass export meat, from cattle grown on their vast lands. Other countries, too, started to specialize their production in those fields in which they were most competitive.

But the first wave of globalization and industrialization also coincided with darker events, too. By the end of the 19th century, the Khan Academy notes, “most [globalizing and industrialized]European nations grabbed for a piece of Africa, and by 1900 the only independent country left on the continent was Ethiopia”. In a similarly negative vein, large countries like India, China, Mexico or Japan, which were previously powers to reckon with, were not either not able or not allowed to adapt to the industrial and global trends. Either the Western powers put restraints on their independent development, or they were otherwise outcompeted because of their lack of access to capital or technology. Finally, many workers in the industrialized nations also did not benefit from globalization, their work commoditized by industrial machinery, or their output undercut by foreign imports.

The World Wars

It was a situation that was bound to end in a major crisis, and it did. In 1914, the outbreak of World War I brought an end to just about everything the burgeoning high society of the West had gotten so used to, including globalization. The ravage was complete. Millions of soldiers died in battle, millions of civilians died as collateral damage, war replaced trade, destruction replaced construction, and countries closed their borders yet again.

In the years between the world wars, the financial markets, which were still connected in a global web, caused a further breakdown of the global economy and its links. The Great Depression in the US led to the end of the boom in South America, and a run on the banks in many other parts of the world. Another world war followed in 1939-1945. By the end of World War II, trade as a percentage of world GDP had fallen to 5% – a level not seen in more than a hundred years.

Second and Third wave of Globalization

The story of globalization, however, was not over. The end of the World War II marked a new beginning for the global economy. Under the leadership of the United States of America, and aided by the technologies of the Second Industrial Revolution, like the car and the plane, global trade started to rise once again. At first, this happened in two separate tracks, as the Iron Curtain divided the world into two spheres of influence. But as of 1989, when the Iron Curtain fell, globalization became a truly global phenomenon.

In the early decades after World War II, institutions like the European Union, and other free trade vehicles championed by the US were responsible for much of the increase in international trade. In the Soviet Union, there was a similar increase in trade, albeit through centralized planning rather than the free market. The effect was profound. Worldwide, trade once again rose to 1914 levels: in 1989, export once again counted for 14% of global GDP. It was paired with a steep rise in middle-class incomes in the West.

Then, when the wall dividing East and West fell in Germany, and the Soviet Union collapsed, globalization became an all-conquering force. The newly created World Trade Organization

(WTO) encouraged nations all over the world to enter into free-trade agreements, and most of them did, including many newly independent ones. In 2001, even China, which for the better part of the 20th century had been a secluded, agrarian economy, became a member of the WTO, and started to manufacture for the world. In this “new” world, the US set the tone and led the way, but many others benefited in their slipstream.

At the same time, a new technology from the Third Industrial Revolution, the internet, connected people all over the world in an even more direct way. The orders Keynes could place by phone in

1914 could now be placed over the internet. Instead of having them delivered in a few weeks, they would arrive at one’s doorstep in a few days. What was more, the internet also allowed for a further global integration of value chains. You could do R&D in one country, sourcing in others, production in yet another, and distribution all over the world.

The result has been a globalization on steroids. In the 2000s, global exports reached a milestone, as they rose to about a quarter of global GDP. Trade, the sum of imports and exports, consequentially grew to about half of world GDP. In some countries, like Singapore, Belgium, or others, trade is worth much more than 100% of GDP. A majority of global population has

benefited from this: more people than ever before belong to the global middle class, and hundred of millions achieved that status by participating in the global economy.

Globalization 4.0

That brings us to today, when a new wave of globalization is once again upon us. In a world increasingly dominated by two global powers, the US and China, the new frontier of globalization is the cyber world. The digital economy, in its infancy during the third wave of globalization, is now becoming a force to reckon with through e-commerce, digital services, 3D printing. It is further enabled by artificial intelligence, but threatened by cross-border hacking and cyberattacks.At the same time, a negative globalization is expanding too, through the global effect of climate change. Pollution in one part of the world leads to extreme weather events in another. And the cutting of forests in the few “green lungs” the world has left, like the Amazon rainforest, has a further devastating effect on not just the world’s biodiversity, but its capacity to cope with hazardous greenhouse gas emissions.

But as this new wave of globalization is reaching our shores, many of the world’s people are turning their backs on it. In the West particularly, many middle-class workers are fed up with a political and economic system that resulted in economic inequality, social instability, and – in some countries – mass immigration, even if it also led to economic growth and cheaper products. Protectionism, trade wars and immigration stops are once again the order of the day in many countries.

As a percentage of GDP, global exports have stalled and even started to go in reverse slightly. As a political ideology, “globalism”, or the idea that one should take a global perspective, is on the wane. And internationally, the power that propelled the world to its highest level of globalization ever, the United States, is backing away from its role as policeman and trade champion of the world.

It was in this world that Chinese president Xi Jinping addressed the topic globalization in a speech in Davos in January 2017. “Some blame economic globalization for the chaos in the world,” he said. “It has now become the Pandora’s box in the eyes of many.” But, he continued,

“we came to the conclusion that integration into the global economy is a historical trend. [It] is the big ocean that you cannot escape from.” He went on the propose a more inclusive globalization, and to rally nations to join in China’s new project for international trade, “Belt and Road”.